Published online Jun 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i6.206

Revised: March 6, 2014

Accepted: May 8, 2014

Published online: June 16, 2014

Processing time: 212 Days and 19.3 Hours

We report a case of a 77-year-old patient with complete atrioventricular block. She underwent permanent pacemaker implantation complicated by right ventricular lead perforation. This was suspected on transthoracic echocardiogram and confirmed by chest computed tomography. The lead was repositioned in the cardiac electrophysiology lab followed by an uneventful course thereafter.

Core tip: Cardiac perforation should be considered in cases of pacing lead malfunction. Chest computed tomography is helpful in diagnosing lead perforation and can be done without contrast and using a small field of view to diminish the effective radiation dose.

- Citation: Nash G, Williams JM, Nekkanti R, Movahed A. Case of early right ventricular pacing lead perforation and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(6): 206-208

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i6/206.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i6.206

Cardiac perforation is a known complication of lead implantation and should be considered in cases of post operative lead malfunction. We present a case of early lead perforation diagnosed by chest computed tomography (CT).

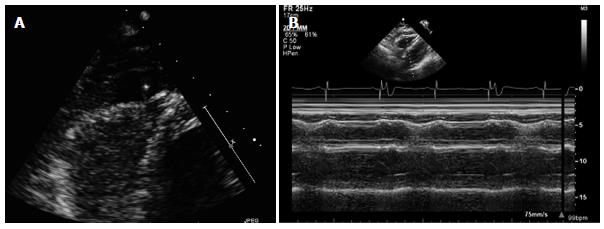

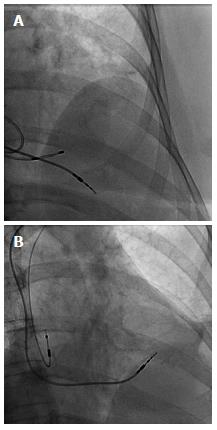

A 77-year-old Caucasian female with a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia and stage 3 chronic kidney disease was brought to the emergency department from home, after her family noticed her “passing out” while seated in a chair. She was noted to regain consciousness within a few seconds. On initial evaluation, her temperature was 36.6 degrees Celsius, blood pressure was 116/61 mmHg, pulse was 43 bpm and regular, respiratory rate was 12 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation on room air was 99%, physical exam was otherwise unremarkable. A sinus node rate of 88 bpm with 2:1 atrioventricular block (ventricular rate of 44 bpm), right bundle branch block and left anterior fasicular block was noted on a 12 lead electrocardiogram (ECG). Exercise myocardial scintigraphy performed one month prior to admission was normal. She was not taking any medications that could cause iatrogenic bradycardia. Ten seconds of ventricular asystole was noted on inpatient telemetry monitoring prompting insertion of a temporary transvenous pacemaker. Six hours later, a dual chamber permanent pacemaker was implanted in the cardiac electrophysiology lab with good post operative sensing and pacing thresholds in the atrium and ventricle. Twelve hours later she complained of left upper quadrant abdominal pain. Inpatient telemetry demonstrated 2:1 atrioventricular block with loss of ventricular capture at high pacing output (Figure 1). Chest X-ray did not show any shift in lead positions. A temporary transvenous pacemaker was reinserted. Ventricular lead perforation was suspected. A transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated an echo bright structure protruding into the pericardial space. However, the images were suboptimal in quality and therefore technically limited to confirm lead perforation. A localized moderate sized pericardial effusion with right ventricular diastolic collapse best seen on M-mode imaging (Figure 2) was also noted. She demonstrated no clinical signs of cardiac tamponade. Non contrast chest CT confirmed lead perforation (Figure 3) with the tip of the right ventricular lead in the pericardial space. The lead was repositioned in the cardiac electrophysiology lab under fluoroscopic and echocardiographic guidance (Figure 4). Follow up echocardiogram revealed no change in the size of the effusion. There was also resolution of right ventricular diastolic collapse. Device interrogation demonstrated stable pacing and sensing thresholds in the right ventricle. The leads remained in stable position on chest X-ray. On follow up 1 wk later the patient was doing well with complete resolution of the pericardial effusion on echocardiogram.

Complications associated with permanent pacemaker implantation include pneumothorax, myocardial perforation, lead dislodgement or fracture, infection, hematoma, erosion and vein thrombosis[1]. The rates of cardiac perforation range from 0.1% to 0.8% for pacemaker leads[2]. One should be alerted to the possibility of cardiac perforation by a pacemaker lead if pacing or sensing malfunction is noted. Most cases of lead perforation happen during or shortly after implant, but cases of late perforation as long as 4.8 years after implant have been reported[3]. Chest X-ray has traditionally been used to evaluate lead positioning in cases of suspected pacemaker lead perforation. Echocardiogram can be used to provide additional information such as extent of pericardial effusion. Another option is a non-contrast chest CT utilizing a small field of view to reduce the effective radiation dose. In a small case series Henrikson et al[4] demonstrated that 64 slice Chest CT was able to make the diagnosis of cardiac perforation by a device lead in all suspected cases. Risk factors for lead perforation include patient characteristics such as female sex, age, small body habitus, thin heart walls; concomitant therapies such as steroids or anticoagulants; implant techniques; and the design characteristics of the lead[2]. Cardiac perforation by a lead can be corrected by repositioning it under fluoroscopic guidance in the cardiac electrophysiology lab, however surgery may be necessary.

This is a 77-year-old Caucasian female with a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia and stage 3 chronic kidney disease who presented with an episode of syncope.

She had an episode of ventricular asystole while in the hospital and underwent permanent pacemaker implantation complicated by lead perforation.

Ischemic, infectious, iatrogenic and endocrine causes of atrioventricular block were ruled out.

The patient had normal electrolytes, thyroid stimulating hormone level and was not on any atrioventricular nodal blocking agents.

A non-contrast chest computed tomography confirmed pacemaker lead perforation.

There were no relevant pathological findings in this case.

The patient underwent permanent pacemaker implantation with subsequent lead revision after being diagnosed with cardiac perforation.

There are other case reports using various imaging modalities to diagnose cardiac perforation by a pacemaker lead.

Cardiac perforation by a pacemaker lead should be considered in cases of device malfunction regardless of the age of the device.

A well done case report. it find no ancillary comments that would aid the readership, continued success with this excellent writing.

P- Reviewers: Marinkovic SP, Sijens PE S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Phibbs B, Marriott HJ. Complications of permanent transvenous pacing. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1428-1432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Carlson MD, Freedman RA, Levine PA. Lead perforation: incidence in registries. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2008;31:13-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Alla VM, Reddy YM, Abide W, Hee T, Hunter C. Delayed lead perforation: can we ever let the guard down? Cardiol Res Pract. 2010;2010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Henrikson CA, Leng CT, Yuh DD, Brinker JA. Computed tomography to assess possible cardiac lead perforation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006;29:509-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |